Learning From Our Commander-in-Chiefs' good choices, and bad ones

There’s no more fascinating or scrutinized topic in American history than presidential leadership. So much is at stake in a president’s decisions. And yet presidents are mere mortals. Though they have teams of advisors and the best resources at their disposal, they’re just as prone as the rest of us to making short-sighted choices. When they do, the results can be grim.

Episodes of presidential leadership generally fall into four quadrants. Presidents may be forced into making good or bad decisions by circumstances, or they may make good or bad decisions by their own initiative. I’ll examine examples of each in history, from the founding of the nation to our current era.

What Abraham Lincoln decided

We tend to praise presidents the most highly for leading effectively in desperate situations. All leaders know that tidal waves of unforeseen circumstances sometimes hit, requiring them to steer the organization (or even a nation) through the turmoil. The most celebrated example of such courage under duress in American history was Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln entered the presidency facing the nation’s greatest crisis: southern secession and the prospect of Civil War. Lincoln had virtually no executive experience, but he rose to the occasion, with a steely determination to save the American Union.

Not that Lincoln was perfect. He struggled to find the right military leaders, as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson made a mockery of the Union army in the first years of the war. But Lincoln learned through the trials, and he finally elevated Ulysses Grant as the commander who could face down Lee.

Perhaps Lincoln’s most brilliant stroke was emancipating the slaves. In doing this, he used unexpected circumstances to take an equally unexpected initiative. Few people, even in the North, envisioned emancipation as an outcome of the war. When elected, Lincoln did not believe that the president had the power to unilaterally free slaves. Lincoln always saw preservation of the Union, not emancipation, as the main goal of the war. But by 1862, he realized that emancipation could help him save the Union. Thus, exercising his power as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, he announced that slaves in the South were free. He encouraged them to abandon their masters and join the Union military, which they did in droves.

Andrew Johnson's stubborn folly

We don’t know whether Lincoln would have thrived as a decision-maker after the war was over, because he was felled by an assassin. But we can assume that he would have done better than his successor, Tennessee’s Andrew Johnson. A series of bad decisions amidst difficult circumstances made Johnson one of the worst presidents in American history. In the aftermath of the war, congressional Republicans pushed to secure basic legal rights for the freed slaves. But Johnson did everything he could to stop such reforms.

The opportunities for liberty presented by Reconstruction bogged down into a petty political war within the northern-dominated federal government. This finally precipitated an ugly attempt to impeach and remove Johnson in 1868. Johnson narrowly avoided removal, but the impeachment crisis drained all remaining momentum out of his presidency. A victim of his stubbornness, Johnson hardly rose to the occasion under difficult conditions.

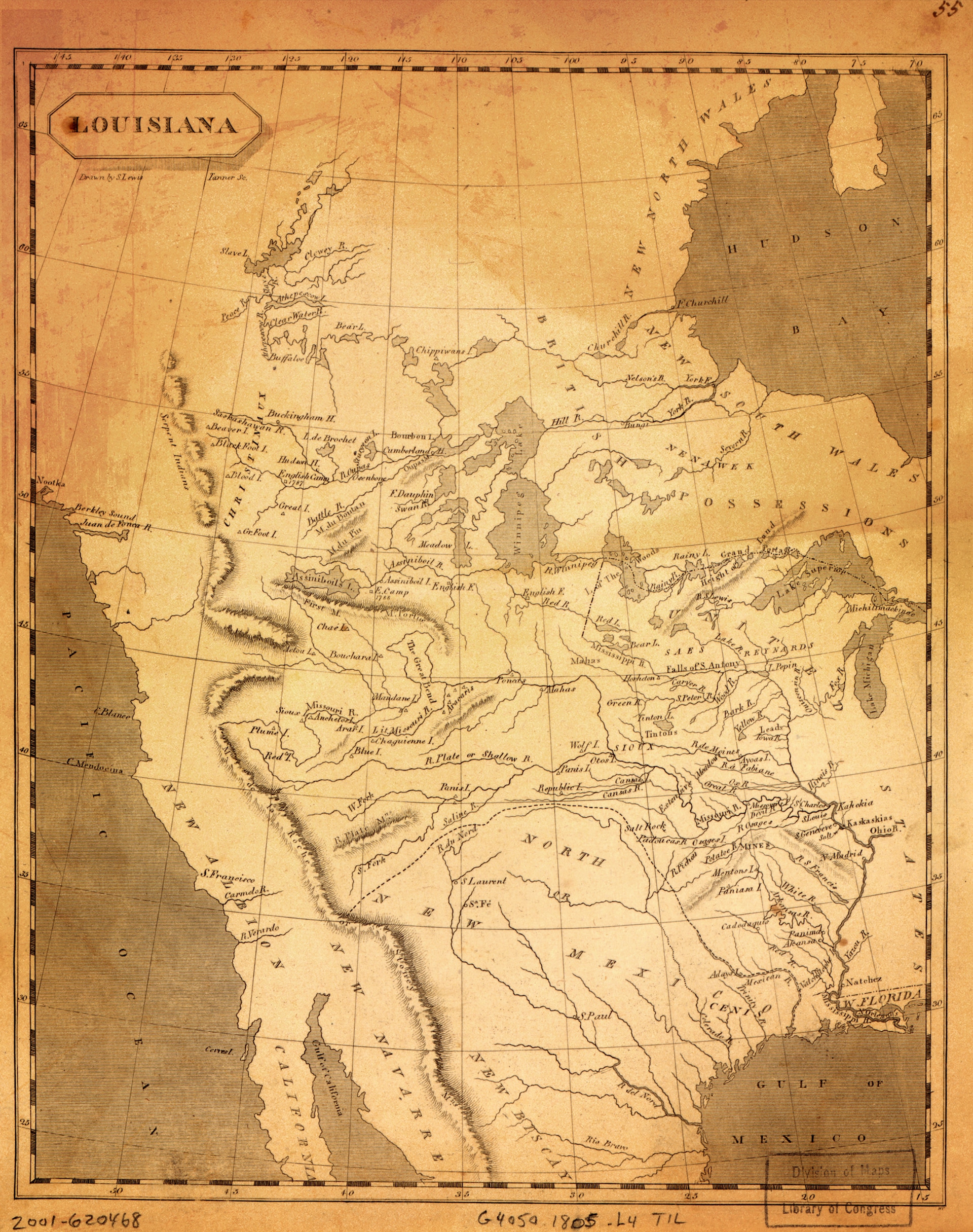

Seizing the moment

Other presidents have distinguished themselves by making valuable changes that their circumstances did not necessarily require. These leaders sensed opportunities that others might not have. One example of this was Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase in 1803. It was not clear that the U.S. had the power under the Constitution to acquire new territory, and Jefferson had previously been quite cautious about expanding the young federal government’s powers. Jefferson’s administration had been working quietly to acquire just the city of New Orleans, but suddenly it became clear that the French might cede the vast Louisiana Territory (most of the land from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains). Jefferson captured the moment, getting the Senate to approve the purchase for $15 million, or 3 cents an acre. It was arguably the best deal ever made by the U.S. government.

In more recent history, Lyndon Johnson also showed remarkable initiative in securing landmark Civil Rights legislation. As a white southern Democrat from Texas, he was not the most likely champion of this transformation (in those days, southern Democrats typically opposed Civil Rights reform). President John Kennedy had originally proposed the Civil Rights Act in 1963, but before his death it was stalled in Congress. Johnson poignantly cited Kennedy’s assassination to push the bill through Congress in 1964. Johnson proclaimed that “no memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.” After the nation’s long night of Jim Crow discrimination, the Civil Rights Act supplied legislative tools to fight discrimination based on race, sex, or religion in America.

Misreading the moment

Ironically, Jefferson and Johnson also initiated bold interventions that turned out to be disasters. In his second term, Jefferson dealt with tensions between the U.S. and Britain which would soon lead to the War of 1812. The British navy was harassing American ships and taking sailors captive. Jefferson’s solution seemed reasonable at first: he embargoed U.S. trade with Europe. Jefferson hoped that this would create hardship for Britain and France, but it had the opposite effect. The embargo boosted European trade with the rest of the Americas, and nearly wrecked the U.S. economy.

For his part, Johnson’s ill-fated decision to escalate American involvement in Vietnam destroyed his presidency. Johnson had not originally intended to do this, but he felt obligated to save South Vietnam from communist takeover. So he got the U.S. more and more involved in South Asia until the prospect of failure risked national humiliation. When the 1968 Tet Offensive showed that Vietnamese communist forces remained formidable, the American public realized that Johnson had led America into a quagmire that cost many American and Vietnamese lives. What was especially galling to many Americans was how pointless the war in Vietnam seemed in retrospect. The exhausted Johnson announced in 1968 that he would not run for re-election.

Choices and consequences

Episodes of presidential leadership generally fall into these four categories: good and bad decisions precipitated by unforeseen circumstances, and good and bad decisions taken on a president’s own initiative. Events shape a president’s course, but sometimes a president takes the lead by his own choice. Either way, the wise and foolish choices that our leaders make define their presidencies and our nation.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.